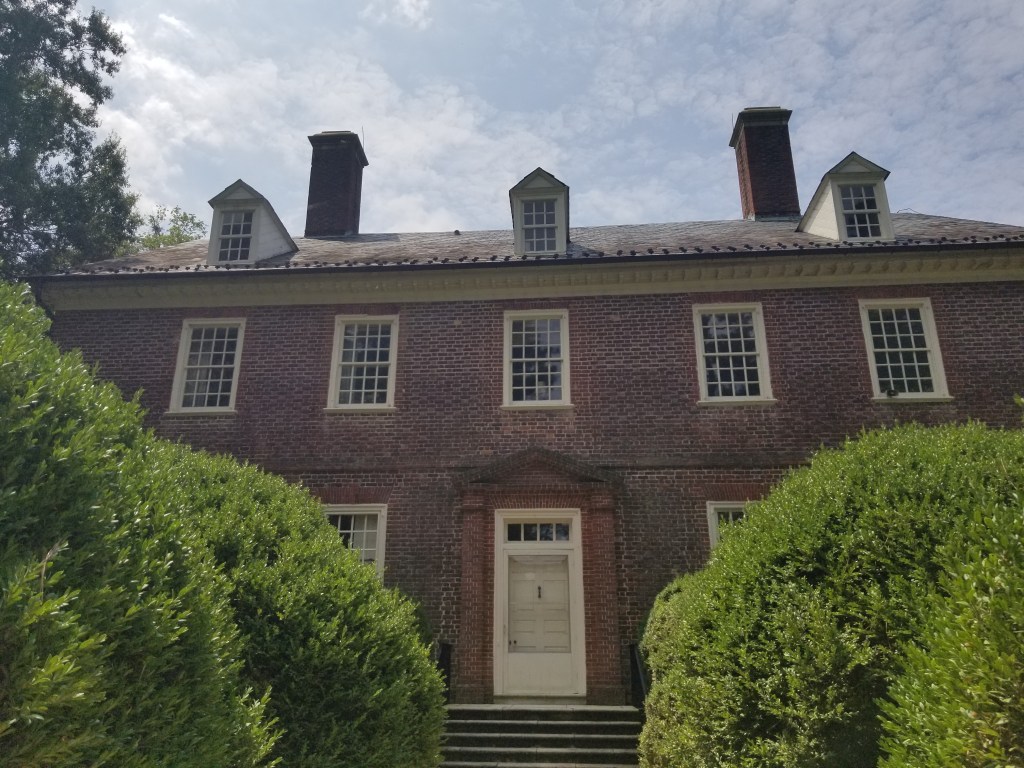

Saturday was Plantation Day. I visited three of the most famous and best preserved James River plantations–Berkeley, Shirley, and Westover. All three are built in the Georgian style of architecture and took at least five years to complete. The reason for the long completion time was that all the construction materials, except the glass windows imported from Europe, had to be made on the property.

Long, tree-lined lanes (covered now with red sandstone gravel, but the dirt would have been unadorned in the eighteenth century) lead into all three plantations. Other than that and their extensive formal gardens, they bear no resemblance to the deep-south mansions we see in movies.

One major take-away from all of them is that when they flourished, the impressive stateliness of the houses and landscapes, set against the beauty of the James River, was superimposed on the backdrop of hundreds of enslaved people who toiled and suffered daily to make the owners prosperous. I sat for a while at the Berkeley Plantation and closed my eyes to listen for their voices–their cries, their songs–seeping up from the quiet fields.

The Berkeley and Shirley are models for properties (with different names) in my novel. I had guided tours of each and took many notes. More than the specifics of each place, much of which I can find in books, I was interested in their “feel.”

What might it have been like to walk the path from the great house down to the river? What would it have felt like to prime or top tobacco plants in the heat and humidity of July while a man with a whip and a quota looked on? What friendships might have been possible? What did possessions look like in both great house and “quarters”? What sense of intimacy/belonging did the rooms give? And, of course, to answer correctly, each question would have to be prefaced by “in the eighteenth century,” a frame of mind which I could only imagine and attempt to recreate based on what we know of the mores of that time.

A few interesting “factoids” I learned from each visit:

Berkeley–

It was originally owned by the Harrison family, which included several notables: Benjamin Harrison V signed the Declaration of Independence and served as governor of Virginia, William Henry Harrison was the ninth US president, and another Benjamin was the twenty-third US president.

In 1726 Benjamin IV married Anne Carter, the daughter of “King” Carter, one of the most successful land owners and slave traders of his time (d. 1732). Planter families commonly married within the “class” to expand their holdings and increase their wealth.

At one time there were at least 110 enslaved Africans on the property. Only the largest plantations owned more than 50 people.

During the Civil War the Union General George McClellan occupied the plantation. One of his generals, Daniel Butterfield, composed “Taps” there. It was originally called Butterfield’s Lullaby.

Some of the bricks used to shine because high temperatures in the kilns gave the surfaces a glass-like patina. Most has worn off over the centuries, but occasionally a glint may appear on a brick when the sun hits it just right. Enslaved people made the bricks as well as all the rest of the building materials.

The first Thanksgiving was actually held here–not Massachusetts–in 1619 after the first settlers arrived on the ship Margaret. Its charter stipulated that upon landing they should give thanks immediately and repeat annually. They did so until 1622 when a Native American uprising massacred most of the settlers.

The entry hall was used as a ballroom and, unlike most of the plantation “great houses,” there is no grand staircase. I was surprised at the relatively small size for what we today consider a ballroom.

Shirley–

The car in the photo belongs to the current residents, tenth generation Hill Carters. They live on the second floor and open only the first to the public.

The land was first settled in 1613. The current “great house” was completed in 1738 and has belonged to the Hill Carter family for ten generations.

Anne Hill Carter (another Anne Carter, this one the daughter of Charles) married Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee and later they became the parents of General Robert E.

The grand staircase at Shirley Plantation is its most notable design feature. It is square and rises three stories.

To stay true to the symmetry required in Georgian architecture, the house is designed with fake doors if necessary to mirror working doors and complete the balance of the space.

In colonial days shutters were installed on the inside of windows. They were added to the outside as decoration only in the late eighteenth century.

Approximately 90 enslaved Africans worked on the property in its heyday.

The plantation was used for the filming of the movie, “Harriet.” The only “slave houses” extant on the property are two cabins constructed for the film.

Westover–

As the house is not open to the public, I was not able to see the inside. Built around 1750, it was the ancestral home of the Byrd family. William Byrd II donated land for the founding of Richmond in the 1740s and Harry F. Byrd was a member of the Virginia senate, a US senator, and the fiftieth governor of Virginia.

The grounds and gardens are the closest to the river of all three plantations.

Fascinating detail. Thanks for the virtual tour.

LikeLike

Chan really enjoyed this! There is so much we don’t know about our history in this country. Thanks so much for sharing.

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike