The Christmas and New Year holidays fell in the time between the end of one farming cycle and the beginning of the next. While much of my commentary below applies to the plantation system in general, I am writing primarily about Virginia. In December, work on plantations there was at the lowest level of the year, with the heavy labor of harvesting, drying tobacco, slaughtering animals, and preserving food, mostly completed for the year.

The enslaved people who made the plantations run looked forward to it. It was a time to rejoice. But, as in all matters, the coin had two sides and both planters and enslaved sought to use circumstances to their own advantage. If we pull aside the curtain of merriment, we see a more complicated picture.

The Planters’ Side

For planters, the Christmas season was a time for reinforcing dominance and control. Two primary means of accomplishing this were shows of paternalism and gift giving, and sometimes an enslaved person was himself given as a gift to a member of the planter’s family. On many plantations, the owners’ families used the occasion of the holidays to distribute a new set of clothes and/or small presents to each person. It was also common for planters to provide fresh meat, fruit, and baked goods, in opposition to the usual rations of salt meat and cornmeal they supplied.

One such owner was quoted as saying, “I killed twenty-eight head of beef for the people’s Christmas dinner. I can do more with them this way than if all the hides of the cattle were made into lashes.” [1] Smart thinking, despite voluminous evidence that most planters did not shy away from using the lashing methodology as well.

While the enslaved were not expected to reciprocate in giving gifts, which would have implied equality, on some plantations they were asked to dance for the planter’s family’s entertainment. Sometimes boxing matches were arranged. However, unlike the gladiators, they were not required to fight until one died.

After all, plantations were profit centers and able-bodied men were at a premium. Owners wanted to maximize production, not diminish it. They recognized the opportunity Christmas offered to do that by incentivizing their enslaved people with the things free workers would have taken for granted—good food, clothing, and time to rest.

Another common practice was to provide liquor and, in some cases, to encourage drunkenness. Alcohol added to the already-high spirits in the “quarter,” as the enslaved living area was frequently named. The planter used this to his advantage as well, seeing it as a way to smooth the news of sales and labor contracts.

New Year’s Day was commonly the time that any contemplated or planned transfers of enslaved people were finalized. Planters who sold or hired their people out for fixed periods—sometimes a year at a time and miles away from family—completed arrangements on that day. Doing this during the holidays, it had been shown, lessened the possibility of violence, suicide, or self-mutilation.

The Enslaved’s Side

The people had extra time during the holiday season, but they didn’t just lie about. They used it to take care of their gardens, to hunt for meat for the family, and to patch and repair clothing as well as bedding and cabins. Ever industrious, they also used the time to create things they could trade. They did all of this under the cloud of fear of the sales they might learn about on New Year’s Day.

Some planters gave their enslaved people travel passes, which allowed them to visit friends or family on neighboring plantations. Whatever the location, the enslaved made music, sang, and danced. In the countries of West Africa, where they or their forebears had originated, celebrating through song and dance was a means of connecting with God and the ancestors. In this country it also was a vehicle for preserving their cultures.

On the coast of North Carolina, the enslaved participated in what they called Jonkonnu, sometimes called John Canoe, John Kannaus, or John Kunering. They dressed in wild costumes and went from house to house singing, dancing, and beating rib bones, cow horns, triangles, and a sheepskin-topped box called the gumbo box. Children woke in the morning and saw John Kannaus, not Santa Claus. [2]

While planters focused on using the jolly holidays as an exercise of dominance and a safety valve to siphon off any spirit of rebellion (as described by Frederick Douglass,) the enslaved’s counterpoint was their use of holiday free time to plan insurrection and escape. Rumors and stories of the Maroon[3] rebellions in Jamaica and Saint Domingue (later, Haiti) had circulated in the American colonies since the 1730s. According to Henry Louis Gates, Jr., scholars have reported as many as 313 rebellions in what became the United States. I have no information to indicate how many of these actually began during the Christmas lull, but it is not difficult to imagine that perhaps some of the planning happened then. Gates’ article on the Five Greatest Slave Rebellions in the United States is here: The Five Greatest Slave Rebellions in the United States | African American History Blog | The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross (pbs.org)

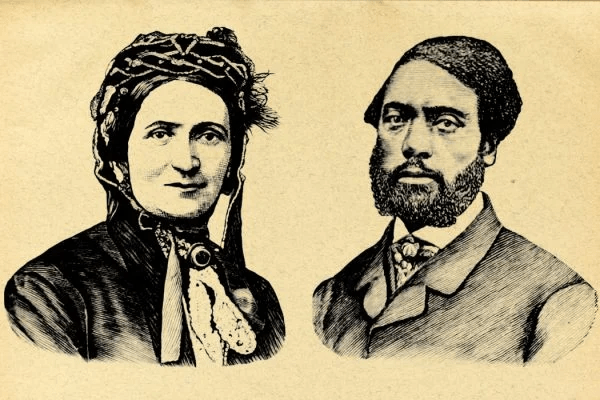

There is, however, specific information on one notable escape that happened during the slack time preceding the holidays. Ellen and William Craft were newly married and afraid any children they might have would be sold away from them, as had happened in William’s own birth family. The couple determined to leave their plantation in Macon, GA and go north to Philadelphia.

Ellen, a daughter of the planter and an enslaved woman, looked white. The couple devised a scheme in which Ellen dressed as a man on his way for medical treatment in Philadelphia and William traveled as his enslaved servant. They arrived on Christmas day, 1848, then soon after traveled on to Boston, a safer haven. This is a much condensed and simplistic account of their daring journey. The author Ilyon Woo has recently celebrated the feat in her 2023 novel, Master Slave Husband Wife.

So, to end where I began, the enslaved looked forward to the slow time leading up to Christmas and New Year’s and to the days in between the two holidays. It was a time to rejoice, to eat well and make merry. But more critically, it was a time to prepare—to arm themselves mentally against the relentless labor they knew would resume in the new year, against the abuse, food scarcity, and constant fear of separation. And it was a time when some prepared for insurrection and escape.

[1] Stephen Nissenbaum, “Battle for Christmas,” quoted by Farrell Evans on History.com

[2] What Was Christmas Like for America’s Enslaved People? | HISTORY; John Kunering at Christmas (cfhi.net)

[3] The word refers to enslaved people who free themselves and create a new community in hiding.

This feels so well researched, Chan. I like how the level of detail brings alive the times and the motivations on both sides. lts a good reminder how our apparent generosity often has mixed motives, including dark ones,

LikeLike

Thanks! Glad you liked it. I appreciate the comment.

LikeLike

Very informative Chan. How’s the book coming along? Can’t wait to read it. Hope you have a wonderful holiday.

Debbie Piscura

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Thanks, Debbie. Book is finished and I’m querying agents. Wish me luck finding the right one. Happy Holidays!

LikeLike

Well written, as per usual, and very interesting. I’ll call when I get my voice back. Second week of covid, mild case, but I’ve lost my sense of taste and smell, makes eating a chore. Julie

LikeLike

Sorry to hear that! Hope it straightens out soon. Glad you liked the piece!

LikeLike