Written in 1900, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was born of the oppression and cruelty of post-Reconstruction Era America. It is a strong, rousing, inspirational song, full of faith and hope. It rings out the resilience and determination of a people striving for acceptance and equality. And, with its final line, “True to Our Native Land,” it declares their patriotism—yes, patriotism—despite constant rejection, vilification, and repudiation. I get chills whenever I hear it and my eyes are unmistakably misted by the end.

The 1890s had been brutal. The Reconstruction Era officially ended in 1877. “Jim Crow” laws had been enacted as early as 1865 and by 1877 were in full steam. Not wasting any time, the Ku Klux Klan had also donned its sheets in 1865. The ten-year period documented nearly 2,000 lynchings.

But the decade also witnessed the rise of prominent African American scholars and activists. Among them, W.E.B. DuBois, Rayford Logan, Frederick Douglass, Fannie Barrier Williams, and James Weldon Johnson, who helped spearhead the burgeoning philosophy of the “New Negro.” These four and others like them fostered belief in racial pride and cultural self-expression, and the right of the people to actively demand political and social equality. They stood in opposition to those like Booker T. Washington, whose mantra was, in modern “technical terms,” “go along to get along;” and Marcus Garvey, who dreamed of a homeland in Africa.

It was in this cauldron that James Weldon Johnson wrote his poem, originally to honor Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. A group of young men were planning a community celebration in Jacksonville, FL, at the Stanton School for Colored Children, where James was principal. It was to include five hundred students. James collaborated with his brother, John Rosamond Johnson, a musician, and they decided to put the piece to music and have all five hundred children sing it.

In his article, “Lift Every Voice and Sing: Why African Americans Stand,” Marvin Curtis quotes from Johnson’s autobiography, Along This Way:

“I got my first line: ‘Lift every voice and sing.’ Not a startling line; but I worked along grinding out the next five…In composing the two other stanzas, I did not use pen or paper. While my brother worked at his musical setting, I paced back and forth on the front porch, repeating the lines over and over to myself, going through all of the agony and ecstasy of creating. As I worked through the opening and middle line of the last stanza:

God of our weary years

God of our silent tears

Thou who hast brought us

thus far on the way

Thou who hast by thy might

Led us into the light

Keep us forever in the path

we pray

Lest our feet stray from the

places, our God, where

we met Thee

Let us, our hearts drunk with

the wine of the world, we

forget Thee…..

I could not keep back the tears, and made no effort to do so. I was experiencing the transports of the poet’s ecstasy. Feverish ecstasy was followed by the contentment—that sense of serene joy—which makes artistic creation the most complete of all human experiences.”

The community in Jacksonville and at large embraced the song. It was later published and became a familiar addition to African American church services and ceremonies of all types. Another kind of social turmoil lifted it to even greater prominence. With the end of WWI, African American military returned home to experience discrimination again after having found respect abroad, especially in France. Racial tensions were high, lynchings were rampant, the Klan had regenerated, and the Great Migration had begun—leading to the “red summer” of 1919.

All this was happening with the “New Negro” Movement playing in the background, rising on the wings of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1919, the NAACP adopted the poem/prayer/hymn and called it the Negro National Anthem. Some in the white community considered it nationalistic and dangerous (Have you listened to the words of the Star-Spangled Banner?) Some African Americans thought it might be a threat to gaining acceptance by whites. James Weldon Johnson disagreed with both camps, saying, “among possibilities are that it may grow in general use among whites as well as colored Americans.”

The photo below shows the Klan in a rally against Catholic immigrants. I include it here because the banner encapsulates the ideology. Does it look familiar?

Later, when the United States was searching for a national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was among the works considered. The Star-Spangled Banner won and became the country’s official anthem in 1931. John Rosamond Johnson had words for those who objected to the continued use of his brother’s song:

“There is nothing in Lift Every Voice and Sing to conflict in the slightest degree with use of Star-Spangled Banner or America (My Country ‘tis of Thee) or other patriotic songs. Music of America is that of the British National Anthem. Music of the Star-Spangled Banner is derived from old foreign drinking songs, difficult to sing; in addition, the sentiments are boastful and bloodthirsty. Words of Lift Every Voice are more elevated in spirit. I do not hesitate to say my brother’s music is better than either of these imported songs.” (Katherine W. Knighten, Music Educators Journal, Vol. 67, No. 6 (Feb., 1981), pp. 38-39 https://doi.org/10.2307/3400634•https://www.jstor.org/stable/3400634.

The song continued to be widely sung and performed until the late ‘50s. When I was growing up, it was a part of every school assembly and special event. With school desegregation, it lost some of its natural platform and “pollinators.” Some younger people thought it dated and “We Shall Overcome” became the rallying cry of the Civil Rights Movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

A revival of sorts began in the ‘80s with the advent of African American History and Studies courses on college campuses, and following the murder of George Floyd, it appears to be experiencing a true renaissance under its new name, the Black National Anthem. This has been helped immensely by none other than the National Football League. Since 2020 the NFL has included a performance of the song in every Super Bowl pre-game show, along with the Star-Spangled Banner. The controversy over “One Anthem,” however, is no less strident now than it was in 1919, as evidenced by social media after this year’s game.

South Carolina U.S. Representative, the Honorable James Clyburn, has proposed adopting “Lift Every Voice” as the national hymn, so far without success. The following analysis by Imani Perry, from her work, May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem explains vividly why the song fits this category:

“Musically, the song reflects how black people were part of the West and yet excluded from so many parts of the lifeworlds of the West. …Rosamond wrote in a major key, but he shifts to a minor key toward the end of each verse, moving the spirit from high to low, from hope to despair. …Rosamond paired sadness with triumph and resilience. The highest notes of the “Lift” are found in the words “rise,” “beat,” and “might,” giving, again, the sensibility of a march, if not the compositional form. …The “break” that begins in the first verse with “sing a

song” has one word for one beat. James’s use of anapestic stresses in the break of each verse (“Sing a song,” “We have come”) also suggests a march, literally if not sonically. It gives the sense of moving in lock step, also marching forward. Also, as Rosamond was classically trained, it is worthwhile to note that this one word–one beat form is reminiscent of an operatic recitative. In making that section speech-like, the song moves from sounding like an anthem to feeling like a mantra. It then finishes with an extended note on the third-to-the-last line of each stanza: “us,” “slaughtered,” and “Thee” in reference to God.” Curtis, Marvin V. “Lift Every Voice and Sing: Why African Americans Stand.” The Choral Journal 62, no. 2 (2021): 43–49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27089733.

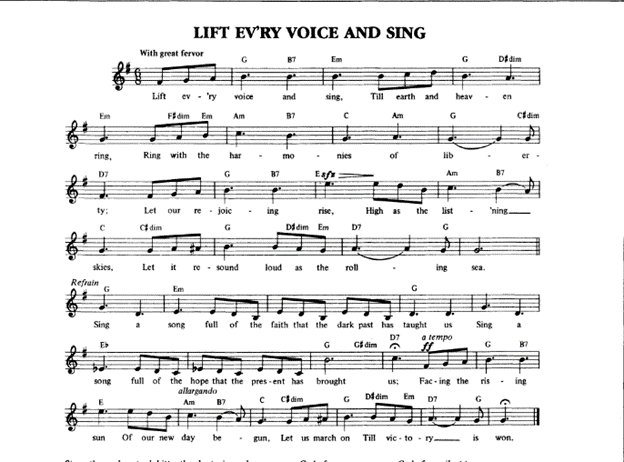

The words to the song:

Lift Every Voice and Sing

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun

Let us march on till victory is won.

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who has by Thy might Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand.

True to our God,

True to our native land.

And, one final note- the following four performances give a taste of the variety of styles, tempos, and arrangements the song accommodates. The last one, by the Winston-Salem State University, is particularly stirring and ends with an “Amen.”

Abyssinian Baptist Church Choir and Congregation, Harlem; Acapella quintet, “Committed,” Oakland University; HBCU 105 voices at Kennedy Center; Winston-Salem State University Choir.

Sources

Knighten, Katherine W. “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” Music Educators Journal 67, no. 6 (1981): 38–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3400634.

Curtis, Marvin V. “Lift Every Voice and Sing: Why African Americans Stand.” The Choral Journal 62, no. 2 (2021): 43–49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27089733.

Congratulations on the scholarship~!

“Stony the road we trod”

“Bitter the chastening rod”

Zetelmo

LikeLike

Well done, Chan. Well done!

LikeLike